We Are Our Own Heroes

Diving into the queerness of the 90s Batman movies + a history of queer identities in comics + queer comic/graphic novel recommendations

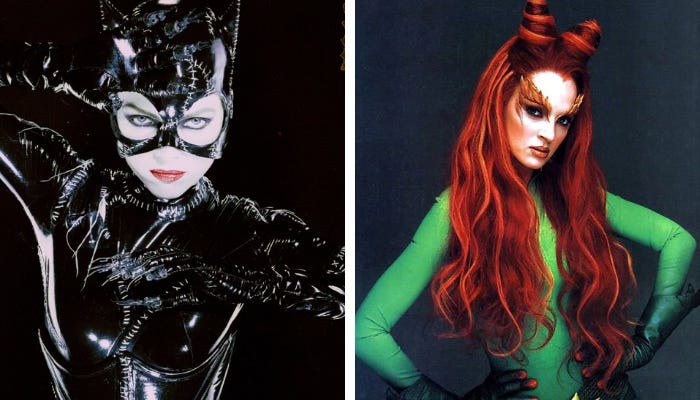

When I was young, I was obsessed with Batman. There was a special action figure of him (with the Batmobile) modeled after the 1992 film Batman Returns that I refused to share with others—it set on a shelf in its pristine glory so I could admire it. I’d watch the film on repeat and feel something when I saw Michelle Pfeiffer as Catwoman. Everyone assumed I had a crush, but no one (not even myself) quite understood the zing that went through me when she swaggered around in her catsuit. The thrill when she delivered the famous line, “Life's a bitch, now so am I,” planted the seed of sass, too.

Looking back, I wanted to be as fabulous Catwoman rather than crushing on her. Then Poison Ivy appeared on screen in Batman & Robin. She made me want to join forces with her without a second thought. Throw in Batman and Robin’s codpieces and the infamous “bat-nipple,” skintight suits that made me question many, many things at a very early age. All of it combined to make it feel like those movies were made for me. Turns out, they were.

I discovered this awhile back when I was reading Glen Weldon’s 2016 novel The Caped Crusade: Batman and the Rise of Nerd Culture. In it, Weldon goes into detail about these films in Batman’s illustrious history from 1939 up until the early 2000s. He notes Uma Thurman (Poison Ivy) considered the role to be equal parts Mae West and a drag queen. The bat-nipples were designed to be so hard they poked out enough to hang kegs on, and the codpieces (not to mention the butts of the suits) were designed to be, well, exaggeratingly hefty.

Weldon says it best with:

“Schumacher (the director of Batman Forever and Batman & Robin)’s two audiences, however, were split not by age but sensibility: 1) gay men and 2) everyone else. In the years since the sixties television show had gone off the air, camp had come out of the closet. It called itself irony now; the era of elaborately coded messages, shibboleths, and innuendo, of embracing the tawdry and tasteless with a fervid flamboyance, of relegating oneself to the role of grotesque, sexless clown, was over. The Stonewall Riots and the AIDS crisis had abraded those filigree edges away, leaving something harder, angrier, and more unambiguously and unapologetically sexual. Thus the much-discussed ‘campiness’ of Batman Forever feels fundamentally different than that of the old television show—less quaint and more defiant. Queerer. The original Batman Forever casting call for Robin, for example, had specified an age range of fourteen to eighteen, which might have established Batman’s bond to the Boy Wonder as strictly paternal. But Schumacher intentionally and gleefully steered into the homoerotic skid. He hired the twenty-four-year-old Chris O’Donnell as Robin and tricked him out with an earring, a tight muscle shirt, and a sneer. The result: a palpable shift in the Dynamic Duo’s dynamic—from a-father-and-his-son to leather-daddy-and-his-piece-of-rough-trade.”1

After reading Weldon’s book in 2016, I fell down a rabbit hole on queer coding in comic books and later movies to better understand (and heal my confused inner child). Somehow, I’d gone my entire life not realizing what’d happened. In an effort to educate myself, I discovered how, for lack of a better word, shitty LGBTQ+ audiences have been treated in this realm.

From 1954 to 1989, the Comics Code Authority (a private organization) had rules against portraying queer characters. Though publishers weren’t legally bound to follow its decisions, suppliers/stores wouldn’t risk carrying a comic without the CCA’s approval. Due to this, it wasn’t until the late 80s that a LGBTQ+ superhero was allowed to appear in mainstream U.S. comic books produced by companies such as Marvel and DC.2 In fact, January 1988 marked the appearance of the first openly gay hero with DC’s Extraño. However, this representation was not done well at all for the queer community.3

The deliberate exclusion of representation was rooted in hate, so much so I cannot bring myself to type that, for another lack of a better word, bullshit here.

That said, it brought about queer coding. This happened because a creator wanted to explore LGBTQ+ themes but faced consequences for outwardly doing so. They were able to address themes by implementing a character with a secret identity, nontraditional relationships with characters of the same sex (side-eying you Batman and Robin), dressing in flamboyant manners, or any other list of stereotypes associated with the queer community. This led to loose interpretations with readers seeing what they wanted to see, which is a great thing.

Until it isn’t.

These queer-coded readings that date back decades aren’t flattering in the least bit. Villains were the focus on coded character themes—and this villainizes queer people. Queer coding brought about queerbaiting, which preyed on queer audiences to spend their money in hopes of seeing themselves on the page or screen (ehem… THE FETISHIZED BAT-NIPPLES!).4

However, queer coding can be viewed as a survival tactic that writers utilized to tell the stories they wanted to tell, albeit their portrayals didn’t lead where they ought to be led. Our queer communities have grown with the changing culture that has deemed coding no longer sufficient. Audiences and creators deserve better than the antiquated mindset that comics have faced. Valid representation must be explicit, and now in 2025 there are a vast array of comics (though not nearly enough) that center queer characters and their lived experiences. More details on them can be found using the Queer Comics Database, a great resource if you’re searching for queer comics to read.

As I gathered my wits after falling down this rabbit hole given the current batshit politics targeting our queer community, I began to think how queer superheroes are extremely important. For so long, our community has been villainized, literally, on page and screen…and now courtrooms and despicable news networks. To showcase these characters being heroes and existing, to have their identities factor into how they perceive saving the world—that can make a difference to a questioning child much like myself. Nothing this important should be shrouded in confusion. It’s imperative we show youth, teens, and everyone else who needs reminding that they are strong too.

We are our own heroes.

Until next time,

M

P.S. Here are some of my favorite queer comics / graphic novels!

The Croaking by Megan Grey is everything I didn’t know I needed, complete with bird people. Yes, bird people. The Roost - the world’s most prestigious military academy - has never accepted a Crow into its ranks. Until now. However, the conditions surrounding Scra’s acceptance are shrouded in conspiracy, and his new roommate Ky won’t rest until he finds out more.

Check, Please! by Ngozi Ukazu details the hilarious and heartbreaking confessions of a figure skater turned collegiate hockey player who's terrified of checking . . . and is desperately in love with the captain of his hockey team. (Of course, this is on my list!)

Lumberjanes by N.D. Stevenson, Grace Ellis, Shannon Watters, and Brooklyn Allen is set at Miss Qiunzilla Thiskwin Penniquiqul Thistle Crumpet's camp for hard-core lady-types where things are not what they seem. Jo, April, Mal, Molly, and Ripley are five rad, butt-kicking best pals determined to have an awesome summer together.

Wynd by James Tynion IV and Michael Dialynas is such a lovely fantasy epic about a boy who must embrace the magic within himself if he wants to save his friends (and the boy of his dreams) from the shocking dangers that await.

The Prince and the Dressmaker by Jen Wang is about Prince Sebastian and his search for a bride―or rather, his parents are looking for one for him. Sebastian is too busy hiding his secret life from everyone. At night he puts on daring dresses and takes Paris by storm as the fabulous Lady Crystallia―the hottest fashion icon in the world capital of fashion.

Bloom by Kevin Panetta and Savanna Ganucheau is a delightful romance set in a bakery, following two young men as they discover love and themselves.

Heartstopper by Alice Oseman is so wildly popular and loved for a reason. Charlie, a highly-strung, openly gay over-thinker, and Nick, a cheerful, soft-hearted rugby player, meet at a British all-boys grammar school.

I have been forced to live with this interpretation of Batman and Robin, and now you do too.

The term “gay” was never used and they later killed him off

This is so important. A few years ago I wrote my research paper centered on gay comic characters and how the whole comicsgate fury didn’t understand the comic books and characters they were mad at.